Common Birds Richard Frater with Scott Rogers and Georgina Steytler at Oracle, Berlin

Galah

I love birds and galahs are one of my favourite species. Why? Because they are loud, beautiful and often behave like lunatics. Unlike most birds that are flat out trying to survive, galahs, like other cockatoos and parrots, seem to spend a considerable amount of time playing. I have seen them hanging from a rope by one foot, twirling around in circles, picking up sticks and throwing them into the air and then leaping up to catch them again and a friend of mine has even seen them sliding down a corrugated tin roof, time and time again, just for the fun of it.

I took my photos of a flock of galahs that live around our town oval, in rural Western Australia. The irony is that they have not always been here. Their natural base used to be much further north, above the ‘mallee’ line as we say. I suspect the reason they can adapt to human environments so readily is the same as the reason they have time to ‘play’, that is, because they are intelligent. Tim Low, in his book titled ‘Where Song Began’ points out that although Australia has threatened birds aplenty, it also has winners, “smart, aggressive birds enjoying the changes people have made”, such as galahs.

“To be effective, any discussion of declining birds must include the winners people see or it will fall on ears turned elsewhere, because Australia is a land in which some of the world’s loudest, smartest and most colourful birds are thriving.”

Georgina Steytler

Rufous Hornero

Rufous Hornero (Furnarius rufus) are one of the most regularly seen birds of Buenos Aires. This species is considered a synanthrope — a creature that draws benefit from living in or around human environments. Hornero, along with Monk Parakeet, Great Kiskadee, Chalk-browed Mockingbird, Rufous-bellied Thrush, and Picui Ground Dove are the synanthropic regulars of Buenos Aires’ parks and gardens. My assumption is that these species, initially adapted for life in savannas and brush, have been able to modify their behaviours as agriculture and then urbanisation changed the places where they live. For a Hornero a park or parking lot can be equivalent to the pampas. However, this is not the case for the vast majority of Argentina’s grassland birds, with numerous species under pressure from soya, hunting, and ranching. So the Hornero is an exceptional case; its numbers increasing with human encroachment. In fact, Hornero are often seen sidling up to humans with an eye for a bread crumb or other morsel from lunch. It was commonplace to encounter them sauntering through the courtyard of the building where I stayed. Occasionally, I observed the species near skips just before garbage collection, probably attracted by leftovers and insects.

Of all the birds of Argentina the Rufous Hornero is probably the most well-recognised as well. It was not unusual to hear small children pointing Hornero out to their caregivers while on a walk in the park. This came as no surprise, as the birds’ plenitude, nest, call, and behaviour do make it distinctive. What did take me slightly aback was the discovery that Hornero hold an esteemed position as Argentina’s national bird. I recognise that my slight sense of incredulity was due to the bird’s humble appearance. This is not a top-of-the-food-chain apex predator such as an eagle. Hornero are gregarious, resourceful, and highly adaptable, but they do not elicit feelings of dread or domination (except maybe amongst insects). As their name suggests, Hornero are also not overtly striking — they are a smallish brown songbird. There are many more colourful, more flashy, more dynamically patterned birds that could be chosen for the country’s mascot.

My assumptions about national birds were subverted in this moment. I was bringing many biases into thinking about these species in general. I had somehow grafted ideas of chauvinism, aggression, violence, or spectacle on to them. I had unconsciously conceived symbolic birds to be show-stoppers — necessarily, rather than being the result of kinder human emotions. Upon reflection, I think the Hornero is a creature that is beloved in Argentina because it brings joy. Hornero seem to be birds that give pleasure, that produce a feeling of happiness for humans. I have the sense that this is the root of their power as a symbol. This was one of the major qualities that motivated me to photograph them.

My photographic efforts were focused on La Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur, the premier birding and wildlife site of Buenos Aires. I took the opportunity to photograph more widely in the city when the situation was conducive, but Costanera Sur has enough to occupy any ornithological enthusiast. The Reserva is an incredible site, recovered organically by vegetation from a failed city planning initiative, and then given protection by the government in the 80s. It is remarkable to see a place such as this, where plants and animals have intensively recolonised a site of urban desolation. Costanera Sur is now considered one of the most significant urban bird reserves on earth, with over 300 species recorded there. The park is intense with life, both human and non-human. It was a pleasant discovery to find wildlife thriving and so many of the city’s residents enjoying the area simultaneously.

Before travelling to Argentina I had intended to hire equipment that I could use for photographing wildlife in the city, such as a Canon 5D with a 100-400mm lens, or a rig of similar construction. I was thinking about a camera that a professional wildlife photographer would use. Once landing in the city, this ideal became a problem. There is certainly equipment like this available in Buenos Aires, but walking around in public with large, obviously expensive gear is an unwise decision. Buenos Aires is very welcoming and friendly, but theft is also a legitimate concern. After having my phone pickpocketed on the subway, I realised a more discrete approach would be needed. I was in luck. My friend Rodolfo offered to let me use his Nikon camera with a 300mm lens. The gesture was very generous, and the camera was totally adequate for the context. I also discovered that bird behaviour in Buenos Aires is quite different to my experiences in Europe. Many species in the city were easily approachable and seemed comfortable, or even curious about my activities. There were a few instances where I couldn’t get the picture I wanted, but these were offset by moments when a Hornero or other beautiful bird was standing right beside me unconcerned.

One thing I had noticed before beginning to photograph is that Rufous Hornero are often heard before they are seen, even through the sounds of the city. I made audio recordings of the birds on several occasions, and their songs are clearly audible above the din of traffic. So while photographing I listened for the calling birds in order to locate them. A bird as vocal as the Hornero is a boon to a photographer, as you always know when there is one around. Hornero are known specifically for their distinctive, chattery duets that increase in tempo and volume. The males and females sing at slightly different speeds, beating their wings at the same rate as their calls. In this way it is possible to determine the sex of the singing birds. Most mornings their calls could be heard as soon as the sun began to rise. There was a pair that regularly visited the rooftop across from my window, entertaining me with sudden eruptions of their vocal jousts.

My time in Buenos Aires coincided with the fledging period for Hornero, when many young birds are testing their wings. Nesting and breeding occur in the early part of the austral summer, and young are out of the nest by January or February — though most fledglings stay near to their place of birth as they mature. As a result I was not able to document the courtship, mating, or nesting behaviours of the birds. This was a little disappointing, as the nest-building activities of the Hornero are particularly fascinating.

Hornero nests hold an iconic position in Argentina. The species in fact derives its name from the unique avian architecture it constructs. The word “Hornero” refers to the Spanish word horno meaning oven. This etymology derives from the similarity between Hornero nests and old-style clay ovens used for baking and cooking. The nests are something of a marvel, and can be found in many places in the city. Over the course of the year Hornero pairs will construct the nests using clay, creating fully enclosed domed structures with a single entrance on the side. This structure’s design has multiple benefits: it prevents predators from gaining easy access; it is highly durable and protected from weather; and it naturally regulates the interior temperature. Other than their form, the other consistent feature of the nests is that they are usually situated in a high up place. It was not unusual to see a clay dome in the crook of a tree at Parque Patricios, but it was equally likely to see one on a lamppost or streetlight. The Horneros seemed to make little distinction. The other fascinating aspect of the clay dome nests is that they are not only a home for the Hornero. Because of their durability, the objects can last for years. Once the Hornero have abandoned them, nests become useful for other species who raise their own young inside. Hornero unintentionally benefit other birds through the sophisticated manipulation of the affordances provided in their environment.

Scott Rogers

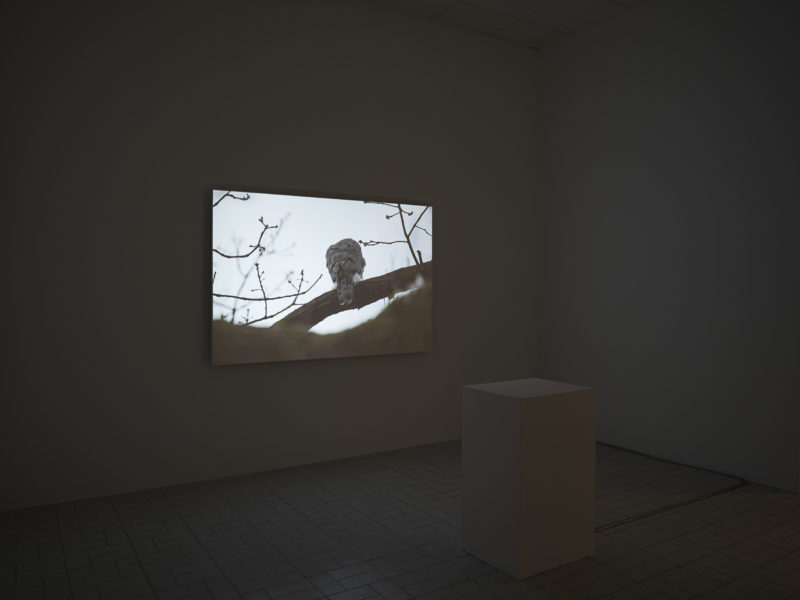

Northern Goshawk

The plan was to observe the goshawks for the sunset and sunrise hours of a weekend, while the light was low. I hired the equipment, chose to trial the new Canon 5D Mark IV with a Canon EF 600/4 L IS and included a 1.4 extender. On the first morning, I followed a call of a female goshawk until I located it on the edge of a grass opening in the canopy, where it stayed. Two hours passed. Nothing happened. I stayed with the goshawks for 12 hours from 7:00-19:00, then I went home. The next day, I followed a similar routine, only I began earlier and left after dark. Often, my eyes simply lost their ability to focus. Even focusing on the goshawk warped the moving tree branches around it like a gigantic fish-eye or shimmering interstellar wormhole. The bird floated inside a sphere. Was this a side affect of staring through the viewfinder too long? I went back Monday morning and squeezed in another few hours of shooting before the equipment was due back. The kwa-kwa started on the train home. I heard it in my apartment. In the bathroom while I showered. It was unusual but so was not speaking to people for two days. Later that night, the goshawks visited my dreams. I don’t recall when the hallucinations stopped.

The northern goshawk (Habicht – Accipiter gentilis) is commonly described as a sedentary bird that breeds in forests. Berlin city is an example of the urban anomaly; it has the largest population of goshawks in the world. An encounter with the reclusive bird in its remote habitat is, self-evidently, rare. Over the past year, I have observed the behaviour of two pairs in the Tiergarten, a park in the heart of the city. This large enclosure provides an adequate spread of mature conifer stands that these birds typically require. But the Tiergarten is only one of the goshawks many habitats. There are over 100 pairs breeding from the outskirt forests to the Hofs and cemeteries of Neukölln. The smallest green island, the Hof, is where the fantasy of an urbanised goshawk has most clearly concretized. What attracts them to Berlin? Hunted prey in forest regions can undergo population build ups and crashes. At the cycle’s end, food shortage can trigger a mass migration of predators. Not strictly a migration, the “flight years” are often referred to as an irruption, invasion or incursion. It is the only time one can observe raptors in groups, all together in a common cause. Forest residents stay in Berlin due to the abundance of their favoured prey. Goshawks are typically shy elusive birds, spotted alone or as a pair during the courtship months, but their urban counterpart has adapted a cooler sociability, unfazed by human presence. My knowledge of where the persuasion begins and ends is limited but predation and threats are minimised in cities. My photos are of F16, F59 and their partners. They are currently in courtship.

20.03.18 Ornithologist Norbet Kenntner on the subject F16: We ringed the male goshawk F16 on a cemetery in the district Schöneberg/Berlin on 23.05.2010 as a nestling. He weighed 660g, had a wing length of 161 mm and was 23 days young. He has one sister (cute). He was only tagged with the ring of the German ringing centre on its left, the coloring project had not commenced at this time. F16 was found injured on 23.12.2017 at the tube station Mendelssohn-Bartholdy-Park, probably after collision with a glass front. He was transferred to a bird rehabilitation centre and released on the 05.01.2018 next to the centre in the east of Berlin, after which he was colorringed on its right leg with F16. He was discovered immediately after release on its breeding territory in the Tiergarten. He weighed 865g. Yours was the 6th sighting of F16 in my database. Please send me the date and location of your sighting, as well as of the colorringed female, including her ring number. I cannot read the coloring of the female on your pics. Please keep the specific breeding grounds of the goshawks secret. It is a special protected bird and it is noncompliant to disturb on their breeding sites by at least two German laws.

The Tiergarten is a green enclosure established in the 16th century. It was first dreamt of as a hunting ground. A fence was built around the existing forest and wild animals were introduced. In 1742, the fences were torn down, initiating a gradual transformation towards the public park model enjoyed today. Over the centuries, commemorative figure sculptures have been installed. Examples from the Romantic, Baroque, and Neoclassicism periods are present, distinguishable by their military uniforms, drapes, and dress codes. More persuasive, perhaps, is the presence of a weathered uniform that the entire stone army radiates. According to moss, history has an ambient tone: all life depends on the chlorophyll-function of the plant. Towards the end of World War Two, over 200,00 old trees were cut down and used as firewood, leaving most of the park naked and neglected. Given its current ecological status––it features more biodiversity than Central Park, New York, and Hyde Park, London––it is a strong example of a non-teleological work in progress. Presently, trees in the park are being thinned for a different purpose: to promote plant undergrowth. Management is fighting against the rising pine forest ecology. But the English-style garden program, which Lenné first inaugurated mid 19th century through ‘picturesque’ landscaping and refurbishment, is still influential today. Stubs of large trees once obstructed pleasurable views. Today, inhabitants of the Tiergarten directly benefit from a lack of funding and resources thrown into the other aforementioned parks, which in these contexts translates to the destruction of habitats.

20.02.18 Excerpts from a conversation with Yorkshire Coast Ecologist Richard Baines: In the 1980’s, in the UK, Goshawks were very hard to see. They were almost mythical birds. We used to travel to the Peak District National Park to see them. I remember seeing my first Goshawk in 1985. It was very exciting and I still hold that feeling. If I started to treat any Goshawk encounter as normal, t would feel like a betrayal. It took these birds a long time to recover from human persecution. I watch them every week in the North York Moors National Park in North Yorkshire but I seldom get close. They are very wary of humans. Berlin is famous amongst birders for your goshawks. When we met in the Tiergarten the female was building the nest. She would break relatively thin branches from the high canopy of a Beech tree and fly with one branch at a time to the nest. The male was calling a lot bringing gifts of food to the female but also keeping his distance. You have to remember she is about 30% bigger than the male and very powerful so he has to choose his movements and timing very carefully.

The territory of the goshawks I followed is full of symbolic eagles. The Bundestag, parliament buildings, the Berlin Zoo and many embassies border the Tiergarten. While walking passed the embassies, it is difficult to ignore the eagles staring at you from, for example, Austria and Egypt’s Botschaften. Germany’s current federal coat-of-arms was designed by Ludwig Gies in 1953. This eagle currently hangs in the Reichstag building. It has developed a bottom heavy bell-like form. Combined with the wings proportion to the body, it reminds me of a pigeon’s anatomy. Sometimes it is called the ‘Fette Henne’. The irony that a hen or pigeon are game for birds of prey will escape most people but these changes were part of a scheme to tone down the symbol’s imperial roots and offer a more friendly appearance. In 1952, just one year earlier, Picasso’s famous dove was spotted perched above Deutschland muss ein Land des Friedens werden on the WBC’s Congress banner in East Berlin, while simultaneously it flew across a mass-distributed blue paper flag in West Berlin. It was intended to be a symbol of peace so it is not surprising it made its way into both of the opposing camps. Legislation of the time supported freeing up the artistic employment of symbols and consequently variations ensued. One variant of Gies’ eagle is visible on the one-euro coin today.

I pondered whether the goshawk has ever been the inspiration for a coat of arms. Besides other characteristics it shares with eagles, it strikes me as a lost opportunity not to exploit how conducive the stone grey and white barring is to graphic reductions. There are a splendid variety of eagle depictions on coins, flags, and letter overheads, post World War II. Responsibility for the national symbol has been intelligently redistributed through democratic ideas of artistry and authorship. And yet, no matter how crude the symbol became––you see a hen, I see a pigeon––each example unequivocally relinks to the former imperial Reichsadler, that which has its genus in the armorial of the Holy Roman Empire. A safe conjecture is that German conservation organisations, which depend on state funded resources, are aware of how the rhetoric of cultural diversity, particularly when it favours Human Rights, can be meld into representing a more ambitious goal for biodiversity. The current version of the Tiergarten supports bio-programs that sometimes contradict each other. Whether you are a consumer who has just wrapped up a days shopping and have taken a moment to view the captive monkeys from the rooftop of the new Bikini complex or you are an ornithologist responsible for the goshawk tagging program, you will have encountered cases of the nature/nurture argument. Zoos construct safe encounters between exotic animals and citizens. They have an ambassadorial function to promote wildlife and diversity. Some citizens might draw hope and inspiration from the captive animals by empathising with their joy and playfulness. Personally, I was moved study this avian resident of the park. For even the goshawks that have entered the monitoring program, the focus is still on freedom of movement and release from captivity, as was the case for F16, and this symbolised something closer to my experience of Berlin.

Richard Frater

Richard Frater

Common Birds

with Scott Rogers and Georgina Steytler

March 30 – May 5, 2018

The 3 participants share an interest in ornithology and birds that have adapted to urban spaces.

3 photographers captured 3 birds on 3 separate continents over a weekend.

Each group of images was given to one of the other photographers for selection.

The resulting slideshow reflects on these examples of shared time.

There is a reader to accompany the slide show.

Download the exhibition reader here

Georgina Steytler

Galah – Eolophus roseicapilla

Western Australia

Canon 1D / Canon EF 600/4 L IS lens

80 of 330 images selected by Scott Rogers

Scott Rogers

Rufous Hornero – Furnarius rufus

Beunos Aires

Nikon / Nikon 300mm lens

50 of 100 images selected by Richard Frater

Richard Frater

Northern Goshawk – Accipiter gentilis

Berlin

Canon 5D Mark IV with a Canon EF 600/4 L IS lens / 1.4 extender

100 of 300 images selected by Georgina Steytler